Tacuinum Sanitatis! Vinegar and fried fish: on the trail of escavèche

Escavèche du Val d’Oise, Momignies

In the region of Charleroi and up to the Botte du Hainaut, there is a dish inherited from a Spanish past which has today become Belgian: escavèche. A fried fish dish, with a vinegar-based sauce, kept in stoneware pots.

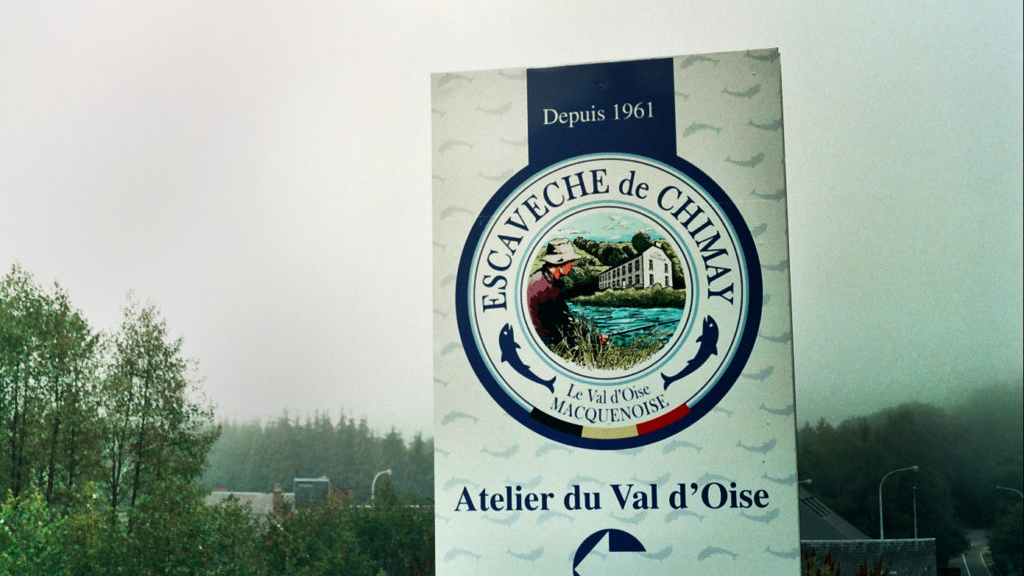

I traced the history of this dish that I didn’t know to find out about its production, history and especially its unique flavour. My journey begins at Macquenoise. A remote village, around 15 kilometres from Chimay, lost in this wild and hilly region. The last Belgian stronghold before the border. That morning, a light fog hung over the landscape. Surprising in this scorching summer. For a few weeks, the whole country had happily forgotten that we were in Belgium.

Today however, the countryside has an autumnal feeling and this morning mist gives me the sense of venturing into mysterious ground on the hunt for a forgotten secret. However, I must be the only one to feel like that as everyone knows about escavèche in this region. It’s a dish that is enjoyed, well-known and renowned.

‘You have arrived at your destination,’ the robotic female voice announces after two hours of driving. I park in front of a small shed. ‘Escavèche du Val d’Oise’, the facade reads. I go to the door and knock. After a few seconds, a face looms behind a steamed-up window. Françoise Meulemeester comes to greet me. Under her white hat, she looks annoyed: ‘Our delivery’s a day late, I wanted to warn you but I didn’t have your number.’

I arrive at the worst moment: ‘Everyone is rushing about.’ But this unexpected delay is rather beneficial for me: I arrive in the heart of the action and can best observe the production process. I follow Mrs Meulemeester along a small corridor and into the production workshop. In a large room covered in aluminium from floor to ceiling, pale smoke is escaping from large stainless steel cooking pots: the sauce is bubbling, the fish is frying. Three women in white outfits are bustling around the ovens. It’s a vision that is both futuristic and traditional. I feel like I’m in a painting by Vermeer: here the milk is in plastic jugs and metal ladles, but the actions are simple and ancestral.

Escavèche is a culinary dish based on fried fish and vinegar, enjoyed throughout the region

Mix, turn over, pour, package. All with a strong smell of vinegar and fish, the two base ingredients for escavèche. ‘You will smell for three days’ one of the cooks told me smiling. The recipe for escavèche is simple: the fish, spiny dogfish, is rolled in flour, fried, put in pots and covered with a sauce made with vinegar, white wine, onions and spices. The actions are quick and precise. In this small company, everything is done manually. The production process has stayed intentionally traditional. An obvious approach for Françoise Meulemeester is to follow family tradition. As a child, she was already helping her parents to make escavèche in the small workshop they had in their house. Nothing to do with today’s modern production methods, designed especially for making the regional dish. And it’s a business which is doing well: three people are employed throughout the year, five during the summer period. No fewer than 20 tonnes of escavèche are produced here per year.

The fried fish is preserved in vinegar

The dish is then sold in regional restaurants and shops, ordered to be served at village celebrations or private events. Escavèche is part of the culture of the country, that’s why, I’m told, it is important to keep it on the menu and to introduce it to people who have not had it before. ‘With a good beer and fries, it’s delicious.’ I want to believe it and I leave the production workshop with a nice stoneware pot given to me by the producers.

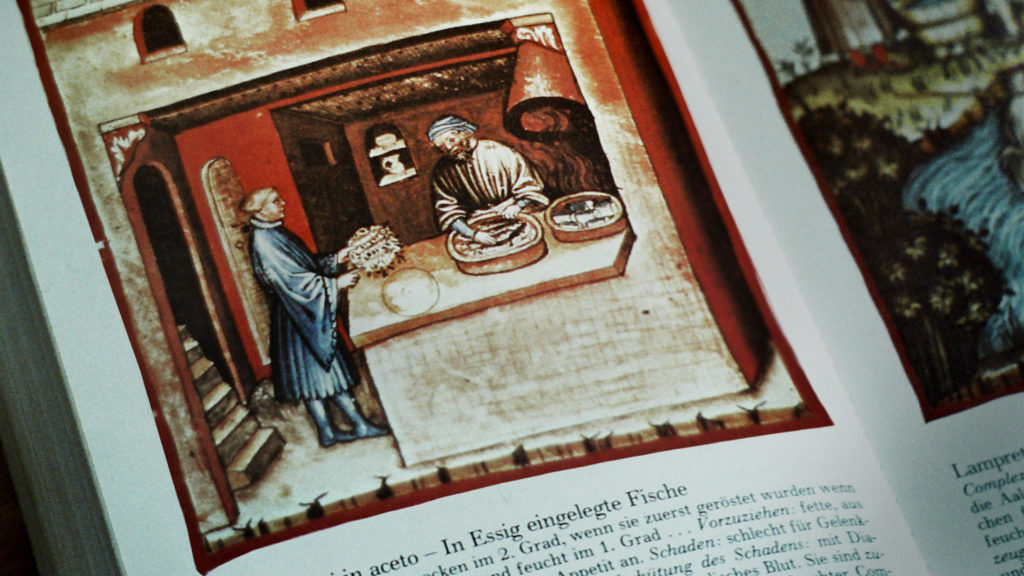

‘Tacuinum Sanitatis’. On the doorstop, Liliane Plouvier, expert food historian, said these words solemnly. ‘Do you know about the medieval medical treaty?’ She invites me in and gives me a small book. ‘Tacuinum Sanitatis, the first manual in which we can see an illustration showing people making escavèche!’ I sit under a valuable tapestry on a quilted seat, and look at the picture carefully. We can see a man putting fish in a pot. The caption says that it is infused with vinegar.

Escavèche tastes good with a good beer and fries

‘The escavèche that we make here is derived from very old recipes. Its origin goes back to the Arab-Persian world. The word also comes from the ancient Persian sikbaj which means vinegar soup or stew. Then it was a meat-based dish that was found on the table of the Persian Sassanid kings. But, being big admirers of the Greek-Roman culture, the Arabs were themselves inspired by an even older recipe.’

I’m like a child whose being told an exciting story. ‘In any event, the idea of a meal preserved with vinegar persists. The recipe then travelled with the Arab conquest to Mediterranean countries and took different forms. In Spain, in the Middle Ages, escavèche was a sort of stew made from fish, vinegar, bread and stolen dried fruit. And in Sicily, during the thirteenth century, King Frederick II bred small fish in Lesina lake so that he could have one of his favourite meals: schabetia. But it’s different from the escavèche of Chimay!’ Liliane goes to her computer. She opens a file containing several documents. I can’t help but read the names of the documents that she is leafing through: sea bream, scampi or artichokes, each ingredient appears to have its own page and information associated with it. ‘Ah, here it is: escavèche!’ She shows me an article which talks about this Sicilian version: ‘It is an absolutely delicious recipe with vegetables and fruit which give it an exquisite sweet and sour flavour. I’ve made it, it’s delicious.’

In my opinion, to enjoy escavèche, you should combine the recipe of Frederick II and that of Chimay.

The passion which causes her to evoke this royal feast is making my mouth water. ‘In Chimay, the recipe is different. It probably dates back to Spanish rule. A book on Liégeois cuisine from the sixteenth century also mentions a recipe that closely resembles the one for escavèche. We can say that this is the first mention of a dish of this type in Belgium.’ I would like to end our interview by returning for a moment to the present day. I ask Liliane, in her capacity as a gastronome, what she thinks should be done to make escavèche more widely popular again. ‘In my opinion, to enjoy escavèche, you should combine the recipe of Frederick II and that of Chimay. You would make an absolutely wonderful dish.’

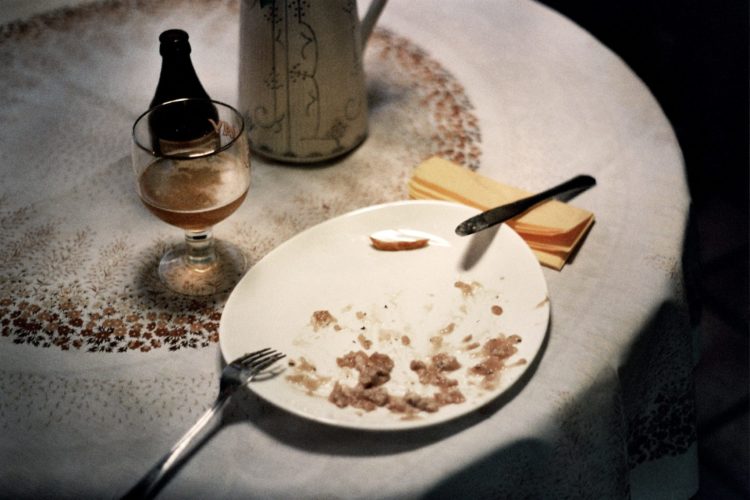

It is 8:00 p.m. when I arrive at my grandmother’s. Native of the Charleroi region, she is very familiar with escavèche. I give her the stoneware pot I was given at the workshop in the morning. ‘I have wanted to eat it again for years!’ There is a Chimay beer and a bucket of finely chopped potatoes on the kitchen table. ‘We often ate escavèche at home when I was a child. I remember this slightly soft fish’s spine that we had with fries. It was very vinegary which makes a child feel sick quite quickly. It was when I had grown up that I learnt to enjoy it.’ She looks at the pot eagerly and removes the elastic band carefully. ‘I remember that we had it delivered to the house. It was in these same large brown stoneware pots. I thought they were beautiful, I wanted to keep them, but at the time, you had to return them, so you could get your deposit back for the empty pots’. I reassure her that this time, she could keep the pot. My grandfather who has in the meantime come into kitchen, shares his knowledge on the subject: ‘It’s a convenient dish. You can open it quickly, eat it straightaway and there’s no waste. It was ideal when it was really hot.’

A man who is hungry knows what his priorities are. My grandmother opens the pot and carefully puts the pieces of fish onto plates. I serve the beer, my grandfather cooks the fries. We sit down together and we eat. The warm fries counterbalance the cold fish, whilst the beer adds a pleasant bitterness. The vinegar sauce has a very particular, very noticeable taste. I am surprised, I have never tasted something like this before. ‘You have to learn to like it,’ my grandfather says, spitting out a bone. I think he’s right. It’s a long way from French cuisine, but I like this simple, practical and very Belgian dish. Because escavèche has this rustic, unpretentious aspect, but also because from all of the stories that I have heard today, I notice that it has added to lives, left its mark on family meals and that it must continue to do that. So escavèche must find its rightful place, amongst carbonade and boulets, grilled endives and mussels, so that it may also be on the list of our most celebrated grub.

Contact :

Escavèche du Val d’Oise

Le Val d’Oise 18

6593 Macquenoise

+32 (0)60 51 11 86

contact@escavecheduvaldoise.be

www.escavecheduvaldoise.be

©Pictures and text/Romain Vannekens